Exhibition

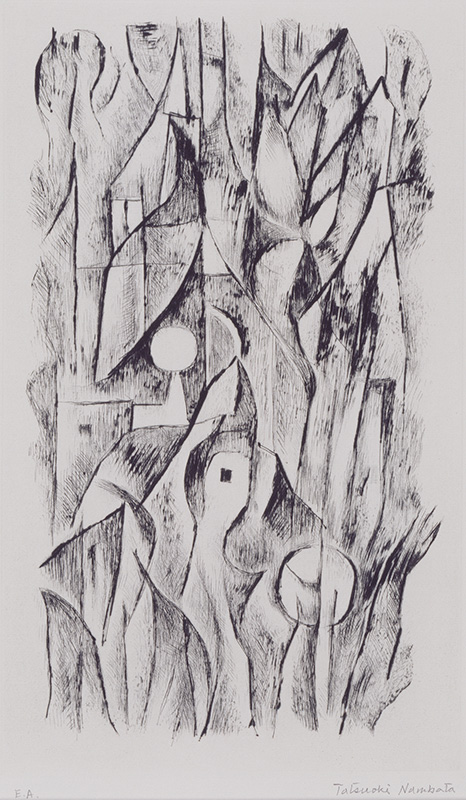

1. Early works and admiration of ancient times

Influenced by his mentor, Takamura Kotaro, Nambata Tatsuoki decided to become a painter, and discovered his own orientation in his Greece series, capturing his fascination for the ancient times that could be seen in Greek sculpture. The style that he developed during this period, paying attention to tone and matiere, remained a part of his practice throughout his artistic career.

1928

Setagaya Art Museum

1935

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo: Kato Ken

1936

Itabashi Art Museum

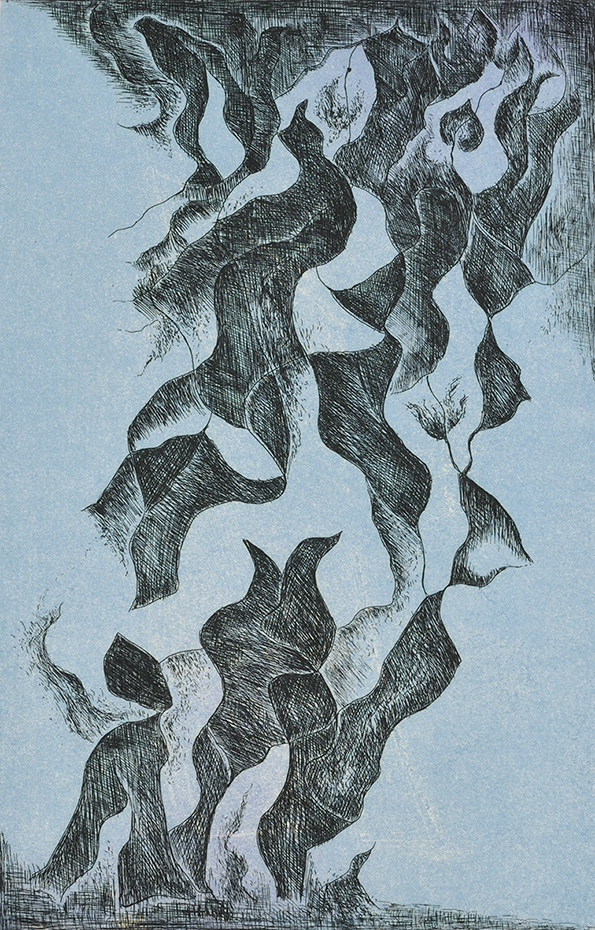

2. Moving closer to abstraction

Tatsuoki had stayed well away from abstract art, but after WWII he begins to experiment, moving closer to abstraction. Discovering new beauty in the city as it recovers in the postwar period, he ponders how to address formal issues while confronting social realities. Still affected by great stress and struggle, he takes up new themes.

1951

Setagaya Art Museum

1956

IKEDA Museum of 20th Century Art

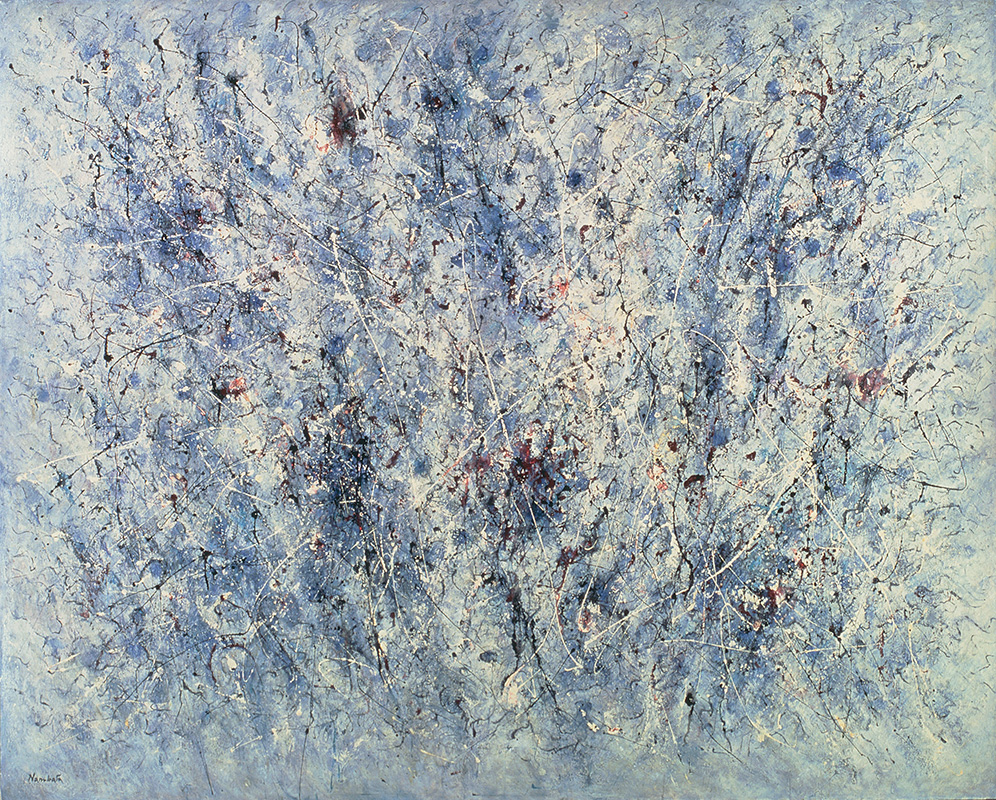

3. Battle with Art Informel and Abstract Expressionism

In the 1950s, Art Informel, Abstract Expressionism, and other new Western abstract movements reach Japan, having a great impact. Tatsuoki took these new ideas seriously, and incorporated some of the techniques, such as dripping, into his own practice. He proceeded cautiously, one step at a time, questioning how they fit in with his own ideas.

1963

Setagaya Art Museum

1965

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

photo: Otani Ichiro

1970

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo: Otani Ichiro

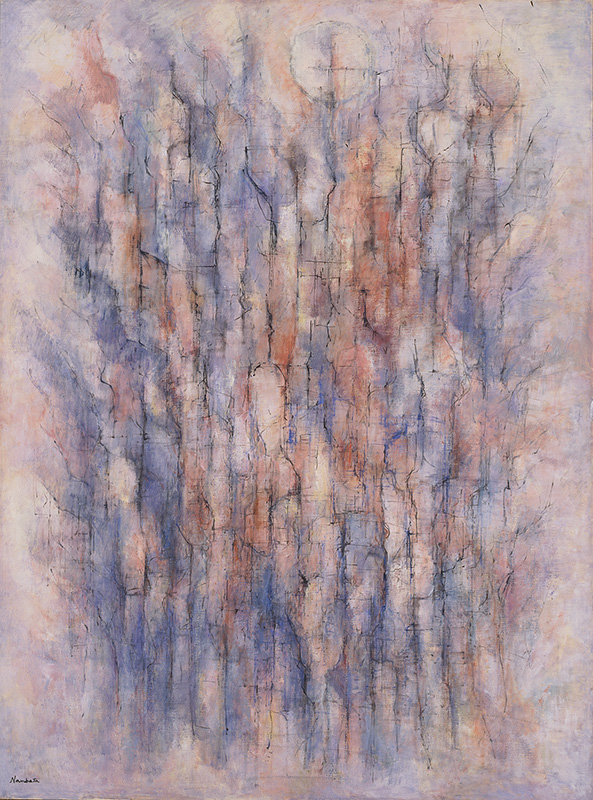

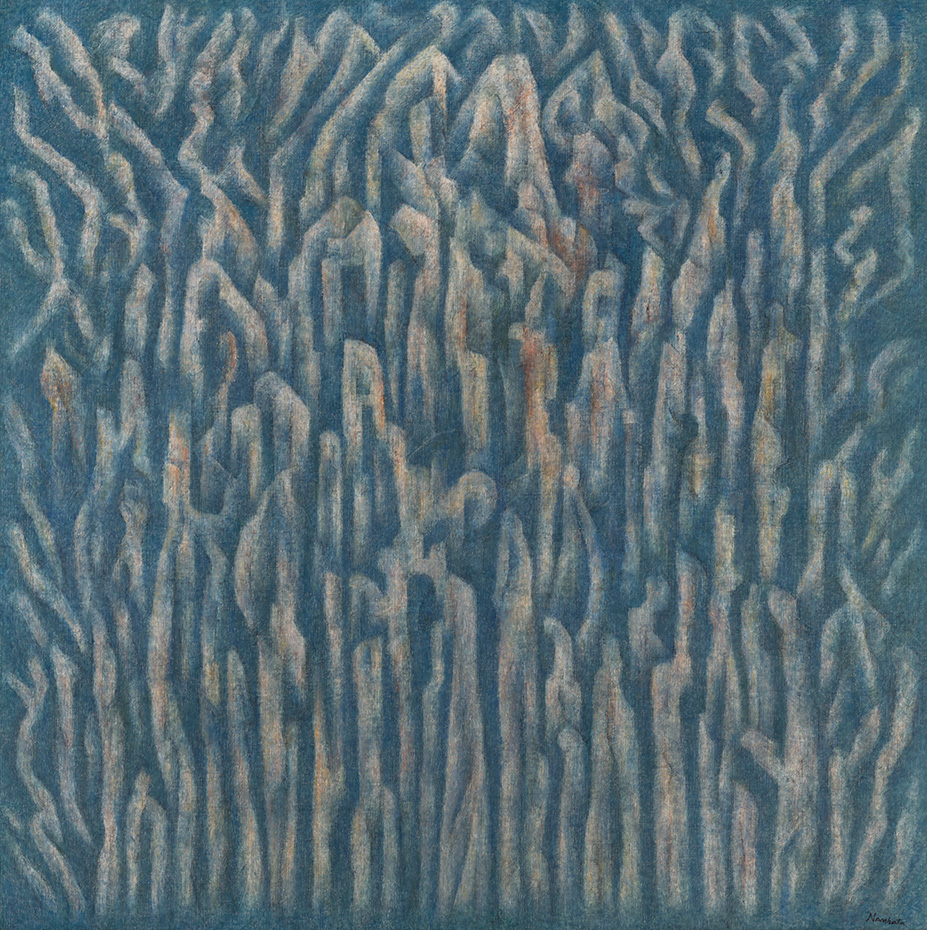

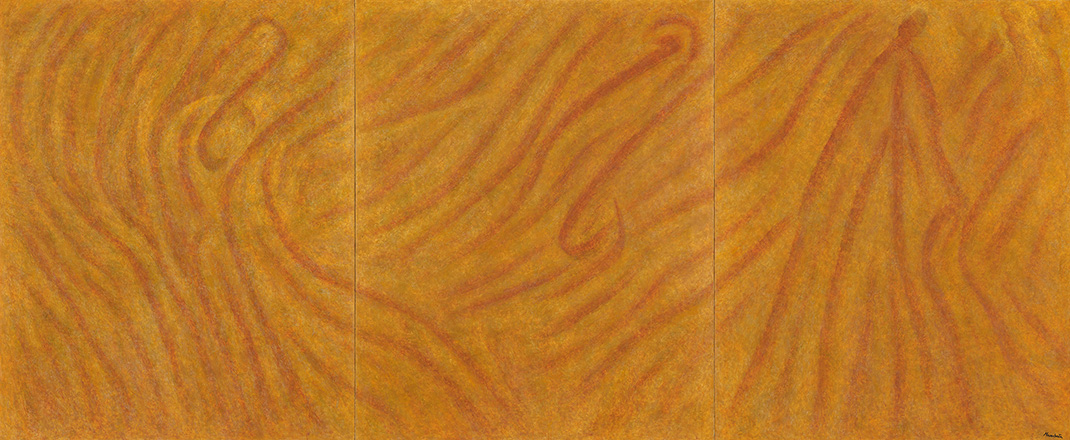

4. Figure and poesy: A distinctive form of abstraction

In 1974 and 1975, Tatsuoki loses his two sons in quick succession. At about this time, he establishes a new approach to painting. The dripping technique that he had been using retreats to the shadows, and instead he focuses his efforts on carefully painted lines and shapes, weaving together colors that expand spatially. This new approach becomes the distinctive style of his practice. These paintings are abstract, but they have a strong sense of the figurative. They mark the confluence of the poesy that had been an indispensable feature ever since his earliest works, with his exploration of forms that incorporate frameworks.

1974

IKEEDA Museum of 20th Century Art

1978

Setagaya Art Museum

1973

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo:Saito Arata

1978

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo: Hayakawa Koichi

1987

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

photo:Otani Ichiro

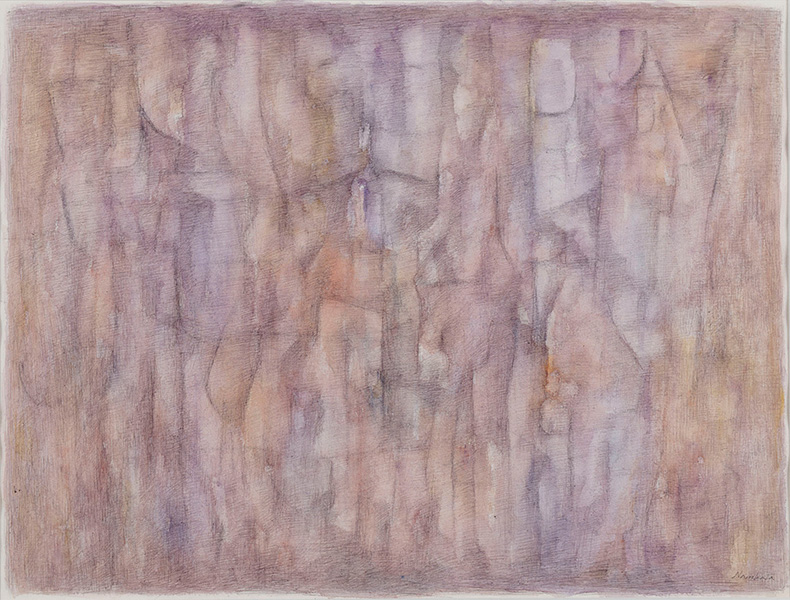

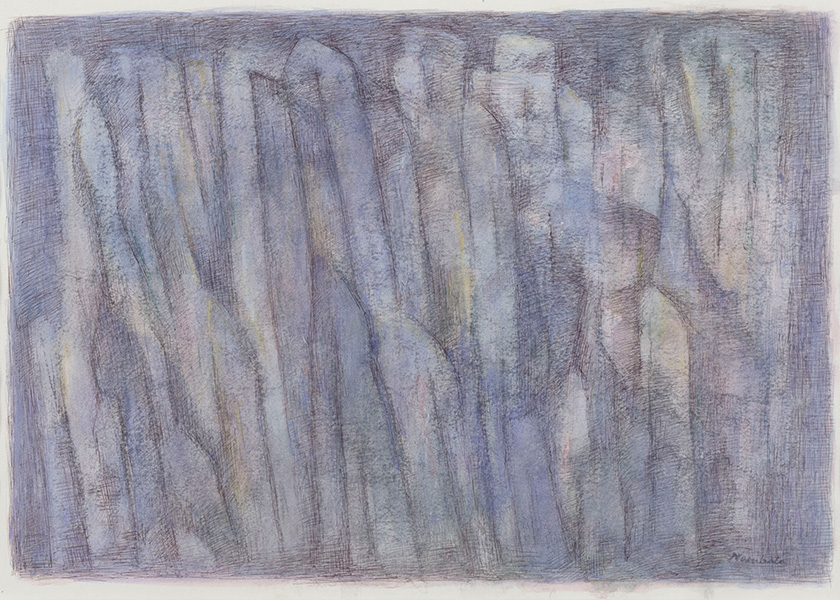

5. The Time in a Stone Cave

Nambata Tatsuoki’s watercolors resemble his works in oils, but they have their own distinctive attraction, with the visual freshness of the images making the paintings seem more familiar, drawing viewers in. The Time in a Stone Cave series of works, commenced in 1988, achieves a mysterious coexistence of the translucence of watercolor with a hardness reminiscent of crystals. Terada Kotaro —donor of the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery's collection— acquired the majority of works in this series, an acquisition that convinced him to begin collecting in earnest.

1988

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo: Saito Arata

1988

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo: Saito Arata

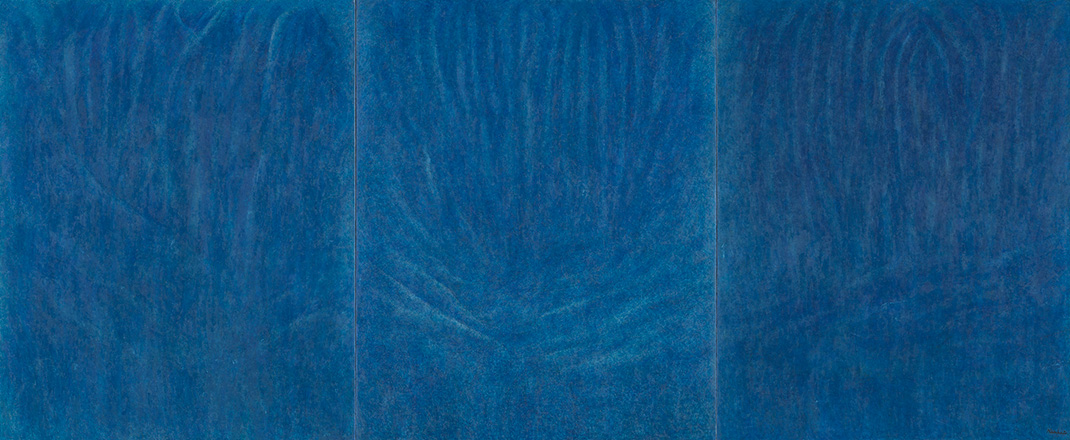

6. Explosion of productivity in later years

In an essay published in 1977, Tatsuoki states “I will paint as long as I can.” Indeed, his production does not deteriorate as he grows older, and he seems to attain a peak in his late eighties. The works in his Record of Life series are inspired by the installation of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies paintings that he sees at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris in 1993 at the age of eighty-eight. This series is an eloquent testimony to his continuing strength.

1994

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo:Wakabayashi Ryoji

1994

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

photo:Wakabayashi Ryoji